By Steve Self, volcanologist, and Paul Renne, geochronologist-petrologist, members of the UCB-BGC NSF-supported Deccan project team

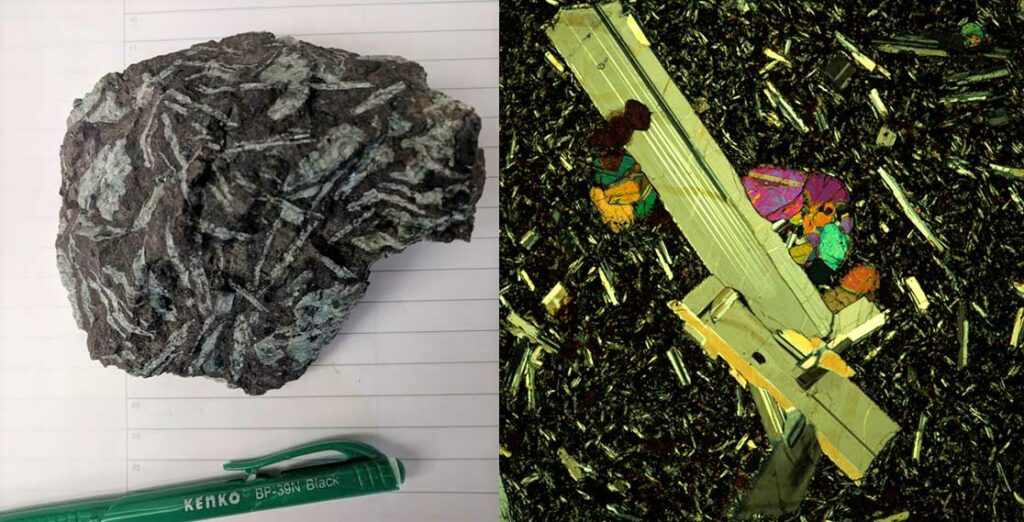

We (Paul and Steve), along with UC Berkeley grad student Andy Tholt and Indian colleagues Kanchan Pande (Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay), Gauri Dole, (University of Pune), Makarand Bodas (Geological Survey of India), and Vivek Kale (private consultant), have been hunting for samples to give us more and more precise age dates for the lava-producing eruptions. Paul has shown that the best targets are the enigmatic giant plagioclase basalts (GPBs), which occur in almost all formations of the Deccan province in west-central India. The large plagioclase crystals (up to 7 cm long and 1 cm thick!) are slightly more potassium-rich than the smaller regular crystals in the Deccan lavas. This improves the chances of getting more precise ages by the 40Ar/39Ar method that Paul has perfected!

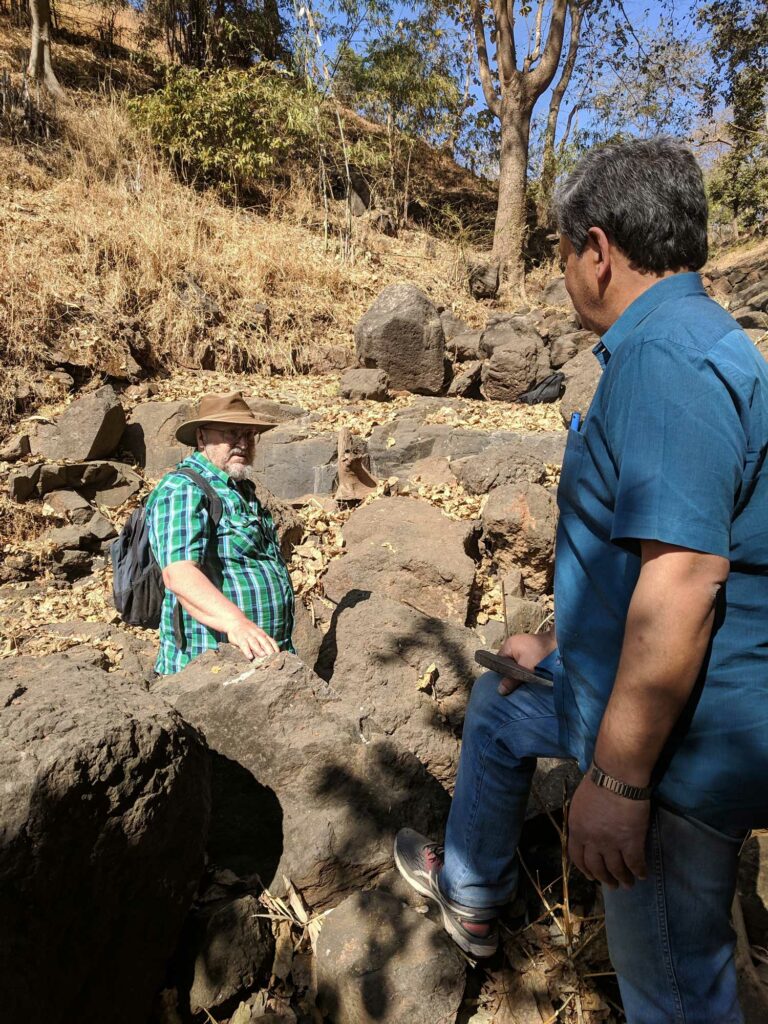

In our field work this January and February 2020 in the Western Ghats or Sayhadri mountains, just before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, we ended up chasing three GPBs in the oldest recognized formations of the Deccan, nicknamed M1, M2, and M3 (M stands for megacryst, i.e. big crystals!). We sampled as far under M1 as possible. We also sampled M2, which is at the top of the Igatpuri formation, and M3 at the top of the Thakurvadi (and/or Bhimashankar) formation.

Contrary to previous assumptions, our observations suggest that lava flows are not “all or nothing” when it comes to GPBs. We found that the GPB is often a zone within a less-GPB-rich lava. Most of the GPBs we saw are clearly not whole lava flows; they are parts of lava flow fields in which some lobes (a lava lobe is a finger of lava that oozes out from a flow and may then merge with other fingers from the same flow) have GPB-characteristics and others do not. This was seen in M1, M2, and M3.

In 2019, we observed that the GPBs seem to be injections into extensive, thick, flat lobes of lava. Our latest observations still support this, although we did see some thinner lobes rich in GPs. The details of this (e.g., % of big crystals in smaller lobes vs. those in thick-lobe-hosted GPBs) deserve a detailed study. One thing we have wondered about is, how the heck do these things, which are so chock-full of crystals, flow? We looked at some basalts where the crystal content is about 65% of the volume of the rock! Now, we think the answer might be that they didn’t start out quite so packed with crystals. Maybe the crystals were injected into a lobe of lava at < 50 % concentration, that liquid then stagnated inside the lobe, and the crystals floated to the top of the injection, making something like we see in the Thalghat GPB (M1) on Thal Ghat itself (see photo below). Anyway, it’s certain that GPBs are quite complex beasts and deserve a lot more attention and mapping out across the Deccan province!

We learned a lot about GPBs on our last road trip, but it wasn’t entirely crystal hunting. Along the way, we appreciated the natural and cultural beauty of west-central India, the geology of which holds so many clues to Earth’s deep history.